The Himalayan mountain range is experiencing an unprecedented winter snow crisis, with meteorologists reporting dramatically reduced snowfall across the region during what should be its snow-heavy season. Scientific evidence confirms that most winters over the past five years have registered below-average precipitation compared to the 1980-2020 baseline, leaving mountains unusually bare and rocky.

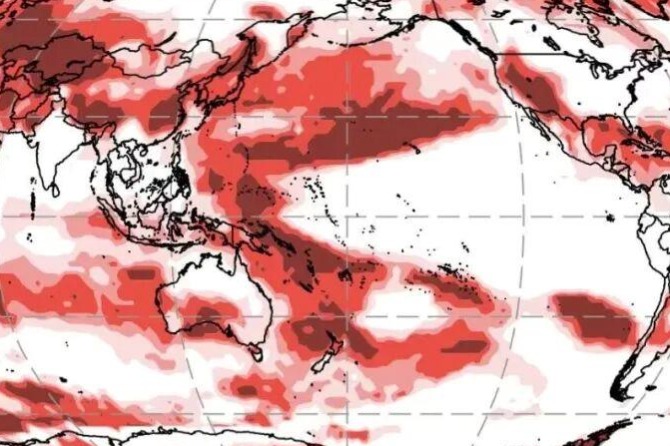

Multiple scientific reports, including those from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, attribute this phenomenon primarily to global warming. Rising temperatures not only reduce snowfall but accelerate melting of what little snow does accumulate. The region is now experiencing what experts term ‘snow drought’ at elevations between 3,000 and 6,000 meters.

According to data from the Indian Meteorological Department, nearly all of northern India recorded zero precipitation during December. Projections indicate an alarming 86% reduction from long-period averages for January through March across northwest India, including Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh.

Dr. Kieran Hunt, principal research fellow in tropical meteorology at the University of Reading, states: ‘There is now strong evidence across different datasets that winter precipitation in the Himalayas is indeed decreasing.’ His 2025 study incorporating four distinct datasets between 1980-2021 consistently shows precipitation reduction across western and central Himalayan regions.

Supporting research from Hemant Singh of the Indian Institute of Technology in Jammu reveals a 25% snowfall decrease in the northwestern Himalayas over the past five years compared to the 40-year average. Nepal’s central Himalayas show similar patterns, with meteorologist Binod Pokharel noting essentially zero rainfall since October and consistently dry winters over recent years.

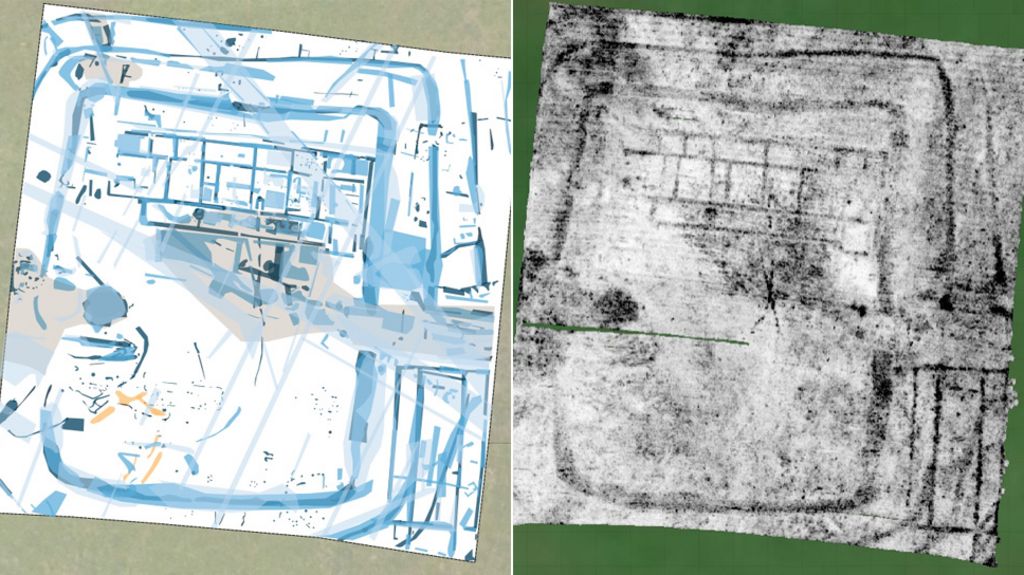

The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) reports the 2024-2025 winter saw a 23-year record low of nearly 24% below-normal snow persistence (snow remaining on ground without melting). Four of the past five winters registered below-normal snow persistence across the Hindu Kush Himalaya region.

Scientists point to weakening westerly disturbances – low-pressure systems from the Mediterranean that traditionally bring cold air and moisture – as a primary culprit. These systems have become ‘feeble’ according to the Indian weather department, tracking northward and failing to collect adequate moisture from the Arabian Sea.

The consequences extend far beyond aesthetic changes to mountain landscapes. Snowmelt typically contributes approximately one-fourth of the total annual runoff for 12 major river basins, meaning nearly two billion people face potential water security threats. Reduced winter precipitation also increases forest fire risks due to drier conditions and destabilizes mountains through loss of ice and snow that traditionally act as natural cement, leading to increased rockfalls, landslides, and glacial lake outbursts.

This snow crisis compounds existing problems from accelerated glacier melting, creating what experts describe as a ‘double trouble’ scenario for the region that will have profound consequences for ecosystems and human populations dependent on Himalayan water systems.