Three decades ago, a clandestine operation unfolded across African skies to repatriate the body of Somalia’s former ruler Mohamed Siad Barre. On the 31st anniversary of this extraordinary mission, the key participants have broken their silence, revealing previously undisclosed details about the politically sensitive undertaking.

In January 1995, Kenyan pilots Hussein Mohamed Anshuur and Mohamed Adan of Bluebird Aviation received an unexpected visit from a Nigerian diplomat at Wilson Airport near Nairobi. The official presented them with an unprecedented request: secretly transport Barre’s body from Lagos, Nigeria, to his hometown of Garbaharey in southern Somalia—a 4,300-kilometer journey across multiple national borders.

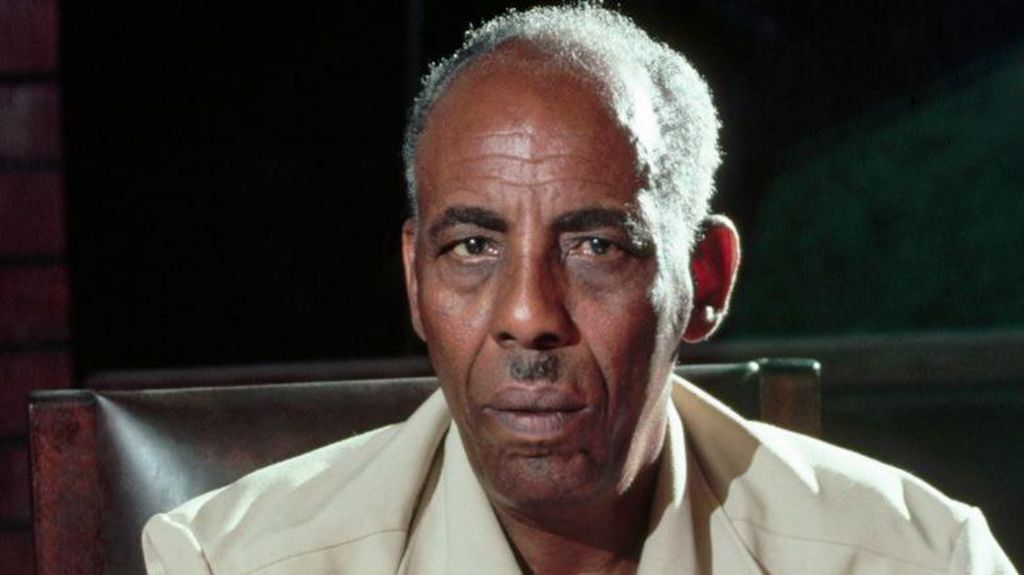

The mission was fraught with political complications. Barre, who had ruled Somalia from 1969 until his overthrow in 1991, died in exile at age 80. Having fled to Kenya initially, he eventually received political asylum in Nigeria under military ruler General Ibrahim Babangida after pressure mounted on the Kenyan government led by President Daniel arap Moi.

Anshuur, a former Kenyan Air Force captain, described the moment they received the request: ‘We knew immediately this wasn’t a normal charter.’ The pilots spent a day deliberating, weighing the considerable risks against the lucrative financial offer. They demanded guarantees from the Nigerian government, including full political responsibility if anything went wrong and the presence of two embassy officials on board.

The operation required meticulous planning. On January 11, 1995, their Beechcraft King Air B200 took off from Wilson Airport with a flight manifest falsely listing Kisumu, Kenya as their destination. Instead, they diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, exploiting limited radar coverage across the region. After refueling, they continued to Yaoundé, Cameroon, where Nigerian diplomats awaited, before finally reaching Lagos.

The Nigerian government provided a military call sign ‘WT 001’ to avoid suspicion when entering Nigerian airspace. In Lagos, Barre’s family including his son Ayaanle Mohamed Siad Barre joined the aircraft for the final leg. The secrecy, according to Barre’s son, was necessary to comply with Islamic burial traditions requiring prompt interment, not to conceal illegal activities.

The return journey retraced the route through Cameroon and Uganda, with the pilots maintaining the fiction of a routine flight. As they approached Kenya, they diverted directly to Garbaharey’s small airstrip, which couldn’t accommodate military aircraft. After attending the burial, the pilots returned to Wilson Airport, reporting a false origin from Mandera, northeastern Kenya, to avoid detection.

Reflecting on the mission, Anshuur noted that technological advancements in aviation surveillance would make such a covert operation impossible today. At 65, he acknowledges he wouldn’t undertake a similar mission now, but remains proud of having fulfilled what he saw as a humanitarian duty to ensure a former leader received proper burial in his homeland.