South Africa faces a profound institutional crisis as parallel investigations reveal alarming evidence of criminal cartels infiltrating the highest levels of law enforcement and government. The suspension of Police Minister Senzo Mchunu—a senior African National Congress (ANC) figure and presidential ally—marks a critical juncture in President Cyril Ramaphosa’s response to systemic corruption allegations within the police force.

The crisis emerged dramatically in July when KwaZulu-Natal police chief Lt-Gen Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi publicly alleged that organized crime groups had penetrated government structures. His testimony directly implicated Minister Mchunu, claiming he maintained ties to crime kingpins and had deliberately dismantled an elite unit investigating political murders. These assertions triggered two separate inquiries: the Madlanga Commission, headed by retired Constitutional Court judge Mbuyiseli Madlanga, and a parliamentary investigation in Cape Town.

Testimony before these commissions has unveiled a sophisticated criminal network dubbed ‘the Big Five,’ allegedly operating a multinational narcotics empire while engaging in contract killings, cross-border hijackings, and kidnappings. Police crime intelligence commander Lt-Gen Dumisani Khumalo testified that this cartel had ‘penetrated the political sphere’ and could manipulate investigations, suppress evidence, and obstruct legal proceedings through connections within the criminal justice system.

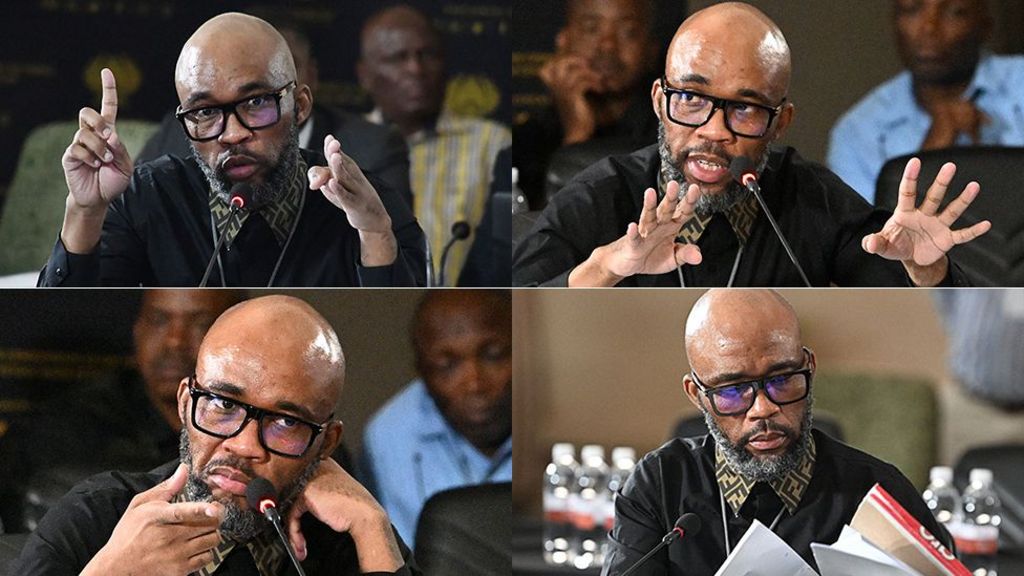

Central to the allegations is controversial businessman Vusimusi ‘Cat’ Matlala, currently facing 25 criminal charges including attempted murder. Witnesses allege Matlala provided financial support for Mchunu’s political ambitions, though both men deny any wrongdoing. Matlala’s testimony before parliament revealed astonishing details about relationships with current and former ministers, including claims that ex-Police Minister Bheki Cele demanded a 1 million rand ‘facilitation fee’ to prevent police harassment—allegations Cele denies while admitting to accepting ‘freebie’ stays at Matlala’s penthouse.

The investigations turned deadly in early December when Marius van der Merwe, a witness who had implicated police officials in torture and extrajudicial killings, was murdered in full view of his family weeks after testifying. His killing highlights the extreme dangers facing whistleblowers in South Africa, where Human Rights Watch documents frequent retaliation against those exposing corruption.

President Ramaphosa now holds an interim report from the Madlanga Commission, though his spokesperson Vincent Magwenya states it won’t be made public until finalized next year. The commission operates in three phases: allegation presentation, response from implicated officials, and witness recall for clarification. With both inquiries continuing into 2026, South Africans await answers about whether their government can effectively address what Gen Mkhwanazi described as ‘terrorism’—criminal elements seeking to control government not through ballots but through illicit means.