The curtain has fallen on the illustrious performing career of Ethiopian jazz luminary Mulatu Astatke, who delivered his final live concert in London last month. The 82-year-old maestro, celebrated for pioneering the distinctive Ethio-jazz genre, concluded a remarkable six-decade journey that transformed global perceptions of African music.

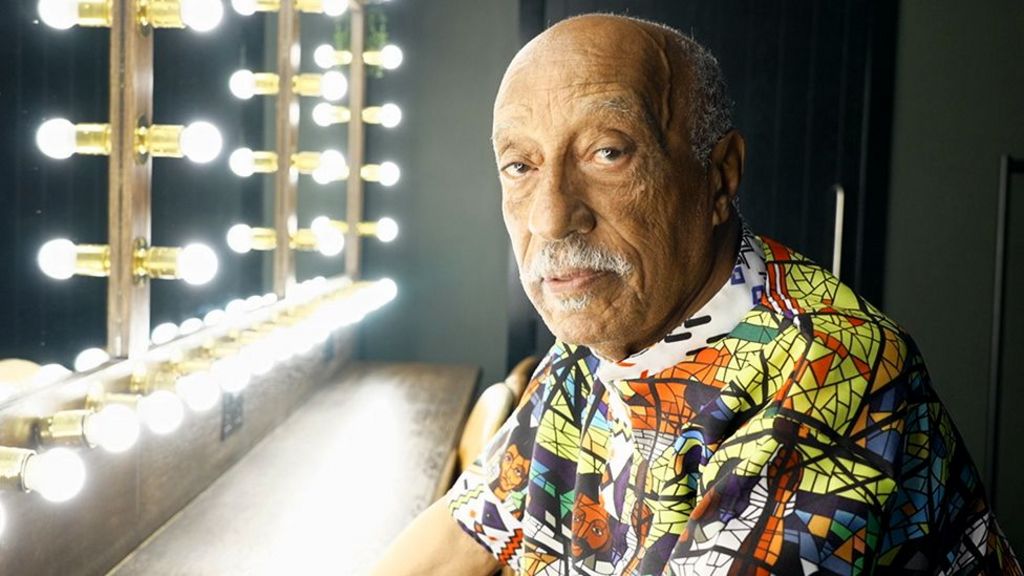

Before an enraptured audience at a West End venue, Astatke—adorned in a shirt featuring artwork by Ethiopian painter Afework Tekle—approached his signature vibraphone with deliberate grace. Navigating past congas, he commenced the evening’s performance with mallets in hand, producing the mesmeric rhythms that have become his auditory signature. The opening piece drew from a 4th Century Ethiopian Orthodox church melody, demonstrating his profound connection to cultural heritage through the pentatonic scales that define his unique sound.

Astatke’s global breakthrough occurred two decades ago when his compositions featured prominently in Jim Jarmusch’s film Broken Flowers (2005). Subsequent inclusion in the Oscar-nominated adaptation of The Nickel Boys further expanded his international audience. Yet his musical experimentation began much earlier—during the 1960s, he transformed recording studios into laboratories where he synthesized diverse musical traditions into what he terms the ‘science’ of Ethio-jazz.

The artist’s educational journey proved instrumental to his innovative approach. After initial studies at North Wales’ Lindisfarne College, he became the first African student admitted to Boston’s Berklee College of Music in the 1960s. There he mastered vibraphone and percussion while incorporating Latin jazz elements. His return to Addis Ababa in 1969 catalyzed the ‘Swinging Addis’ era, during which he fused Ethiopian modalities with Western jazz conventions despite initial resistance from traditionalists.

Throughout political upheavals, including the 1974 deposition of Emperor Haile Selassie that prompted many musicians to emigrate, Astatke remained in Ethiopia continuing his artistic mission. He attributes his deepest inspiration to traditional musicians he reveres as ‘scientists,’ incorporating indigenous instruments like the washint flute, kebero drum, and single-stringed masenqo fiddle into his compositions.

Contemporary admirers recognize Astatke’s enduring influence across generations. London-based fan Juweria Dino notes that his recordings serve as primary introductions to Ethiopian culture for many international listeners. While acknowledging bittersweet emotions surrounding his retirement from touring, devotees emphasize that his legacy will persist through recordings and ongoing efforts to digitize traditional Ethiopian instruments.

The artist himself remains committed to promoting Africa’s cultural contributions, asserting that the continent’s musical innovations deserve greater recognition. Though his concert appearances have concluded, Astatke affirms this transition marks not an endpoint but rather a new chapter in his mission to globalize Ethiopia’s rich musical heritage.