In the remote village of Papiri in Niger state, anguished parents maintain a fearful vigil outside St. Mary’s Catholic School, their silence speaking volumes about Nigeria’s escalating kidnapping epidemic. Their children—among them five-year-olds—vanished ten days ago when armed militants stormed the boarding facility under cover of darkness, part of a disturbing resurgence of mass abductions plaguing north and central Nigeria.

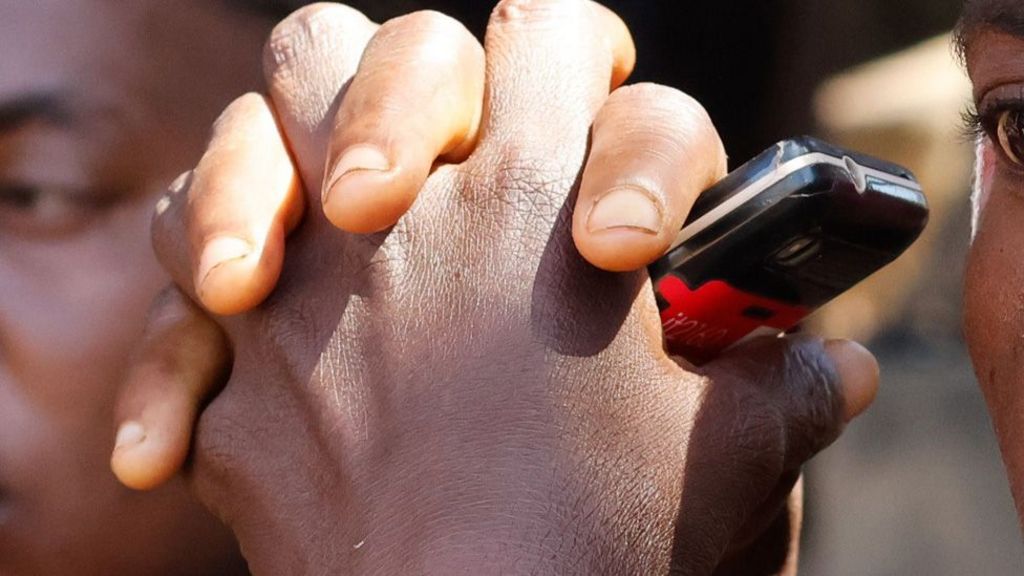

Over 300 students were taken in the November 21 raid, with approximately 250 reportedly still missing despite official claims that numbers are exaggerated. The BBC has spoken with terrified parents who refuse to be identified, fearing brutal reprisals from captors they know operate just three hours from their community. “If they hear you say anything about them, before you know it they’ll come for you. They’ll come to your house and take you into the bush,” shared one father identified only as Aliyu, whose son remains among the missing.

This incident follows a similar pattern to the abduction of 25 girls from Maga in Kebbi state just days earlier, though those students were subsequently rescued from a farm settlement by security forces. While no group has claimed responsibility, the Nigerian government suggests jihadist elements rather than conventional bandits may be behind these operations—a distinction that matters little to traumatized families.

The crisis has forced remote communities to develop extraordinary survival strategies. After enduring a decade of violence with minimal government protection, some villages have initiated unprecedented peace negotiations with their tormentors. In Katsina state, communities like Jibia and Kurfi have brokered fragile agreements where bandits guarantee safety in exchange for access to resources—including mineral-rich lands and market privileges.

Security analyst David Nwaugwe of SBM Intelligence explains: “Those communities severely affected by mass kidnappings have struck so-called peace deals with these bandits in exchange for access to mines.” Northwest Nigeria contains significant untapped mineral deposits, particularly gold, creating profitable opportunities for armed groups.

These negotiations—conducted under shade trees with armed bandit leaders present—have yielded tentative successes. Schools have reopened, hostages have been released, and violence has decreased in participating areas. Bandit leader Nasiru Bosho, who participated in Kurfi talks, stated: “We are all tired of violence. We have agreed to live and let live.”

However, security experts warn these local solutions may simply displace violence southward toward more economically advantaged regions where ransom payments are more substantial. The situation remains further complicated by international factors, including recent comments from U.S. political figures that Nigerian officials insist oversimplify the complex religious and criminal dynamics at play.

As Christian Ani of the Institute for Security Studies notes: “Nigeria’s security situation is now very complicated. We don’t know how to draw the lines between violent extremist groups or bandits because they operate almost in the same areas and in a fluid manner.”

For now, desperate parents in Papiri continue their vigil, hoping for their children’s safe return while larger solutions remain elusive in Africa’s most populous nation.