Shirley Chung, a 61-year-old woman born in South Korea, was adopted by a US family in 1966 when she was just a year old. Her biological father, an American serviceman, left shortly after her birth, and her mother, unable to care for her, placed her in an orphanage in Seoul. Shirley grew up in Texas, living a typical American life—attending school, getting a driver’s license, and working as a bartender. She married, had children, and became a piano teacher, never questioning her American identity. However, in 2012, her life unraveled when she discovered she was not a US citizen after losing her Social Security card. This revelation left her feeling betrayed by the adults in her life who failed to secure her citizenship. Shirley is not alone. Estimates suggest that between 18,000 and 75,000 American adoptees lack citizenship, with some even unaware of their status. Many have faced deportation to their birth countries, with tragic consequences, such as the case of a South Korean adoptee who took his own life in 2017 after being deported. The issue stems from historical gaps in adoption laws. While the Child Citizenship Act of 2000 granted automatic citizenship to adoptees born after February 1983, those adopted before then were excluded. Advocacy groups have been pushing for legislative changes, but efforts have stalled in Congress. The problem has intensified under President Donald Trump’s administration, which has prioritized deportations, leaving adoptees and their families in fear. Shirley and others like her are calling for compassion and action, urging the government to fulfill the promise of citizenship made to them as children.

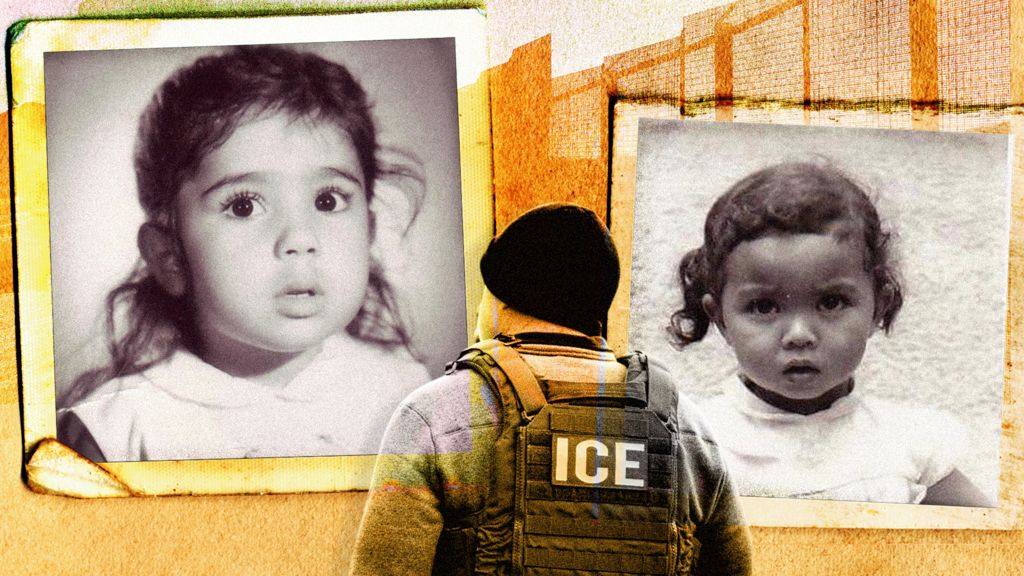

The American adoptees who fear deportation to a country they can’t remember