India has launched an ambitious 73-billion-rupee ($800 million) strategic initiative to establish domestic production of rare earth magnets, aiming to reduce its critical dependence on Chinese supplies in this vital segment of the global supply chain. Approved in November 2025, this comprehensive scheme represents India’s calculated response to vulnerabilities exposed during recent trade tensions with China, which temporarily disrupted supplies to automotive and electronics manufacturers.

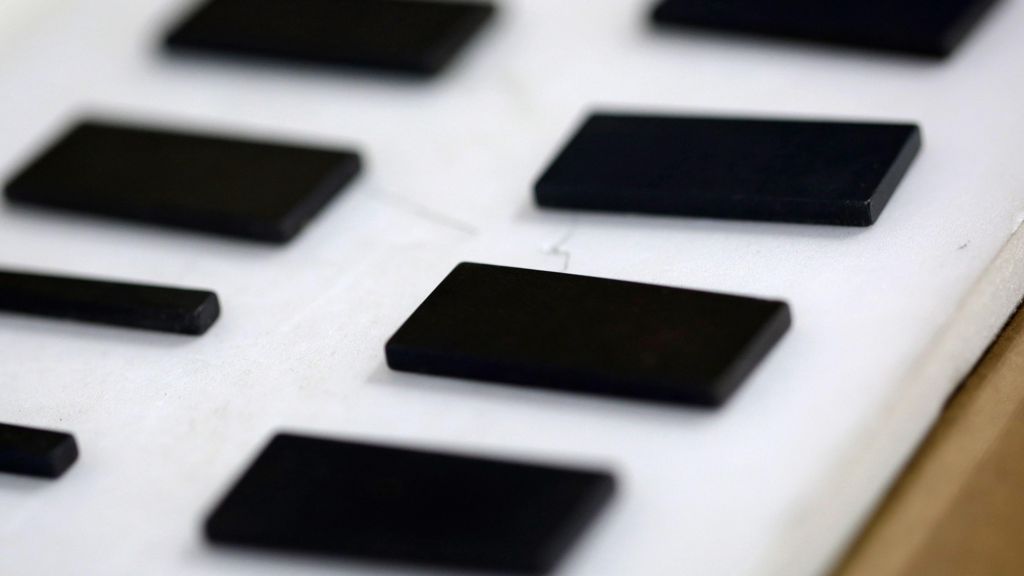

These powerful permanent magnets serve as essential components across multiple high-tech industries, including electric vehicles, wind turbines, smartphones, medical imaging equipment, and defense systems. Rather than attempting to develop a complete rare earth ecosystem—an enormously complex and capital-intensive undertaking—India is strategically focusing on magnet production as the most efficient path toward achieving meaningful self-reliance.

The program offers capital investment and sales-linked incentives to selected manufacturers targeting annual production of 6,000 tonnes within seven years. This production target aligns with projected domestic demand, which government officials anticipate will double within the next five years. Currently, India imports 80-90% of its magnets and related materials from China, which maintains overwhelming dominance with over 90% of global rare earth processing capacity. Official data reveals India imported approximately $221 million worth of these critical components in 2025 alone.

Despite substantial financial commitment, industry experts emphasize that monetary investment alone cannot guarantee success. India faces significant technological hurdles, as countries like Japan, South Korea, and Germany have spent decades refining their magnet production capabilities. Neha Mukherjee of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence notes: “This initiative represents a positive directional step, but merely a beginning. India will require strategic international partnerships to import technology, develop workforce expertise, and ultimately build indigenous capabilities.”

Raw material availability presents another formidable challenge. Although India possesses the world’s third-largest rare earth reserves (approximately 8% of global total), it accounts for less than 1% of worldwide mining output. Most reserves exist in coastal sands across Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Gujarat. Currently, only one operational mine exists in Andhra Pradesh, whose output was predominantly exported to Japan until recent government intervention to prioritize domestic needs.

Furthermore, India’s mineral profile complicates production ambitions. While the nation has surpluses of lighter rare earth elements like neodymium, it lacks extractable quantities of heavier elements including dysprosium and terbium—critical components for high-performance magnets. This imbalance raises fundamental questions about whether domestically manufactured magnets might still rely on Chinese raw materials.

Competitive pricing represents another crucial consideration. Chinese magnets benefit from established economies of scale and lower production costs. Unless Indian manufacturers can achieve comparable pricing through government support and efficiency gains, imported magnets may continue dominating the market. Some experts suggest extending incentives to magnet purchasers alongside manufacturers to stimulate domestic adoption.

India joins a growing global movement seeking alternatives to Chinese rare earth dominance. The European Union, Australia, and other nations have launched similar initiatives following supply disruptions. As EY India specialist Rajnish Gupta observes: “The timing of China’s export controls surprised many nations, highlighting shared vulnerabilities in critical supply chains.”

Despite the multifaceted challenges, the program signifies India’s serious commitment to developing strategic autonomy in this crucial technological domain. As Dr. PV Sunder Raju of the National Geophysical Research Institute emphasizes: “Strong research and development foundations are essential—simply allocating funds cannot guarantee viable production.” Research facilities including a recently inaugurated unit at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre and public-private partnerships aiming for 5,000-tonne annual production by 2030 demonstrate progress, though neither has yet reported commercial output.

The initiative’s success will ultimately depend on India’s ability to simultaneously master complex technologies, secure reliable material inputs, achieve competitive scale, and develop entire supply chain ecosystems. While the path forward remains challenging, as Mukherjee concludes: “If capacity scaling doesn’t occur, dependency persists. China continues expanding production—India must match this growth trajectory to achieve meaningful independence.”