In a strategic maneuver that reveals the complex dynamics of US-China technological competition, the Trump administration’s conditional approval of Nvidia’s H200 AI chip exports to China has produced unintended consequences, ultimately strengthening Beijing’s resolve for technological independence rather than creating diplomatic leverage.

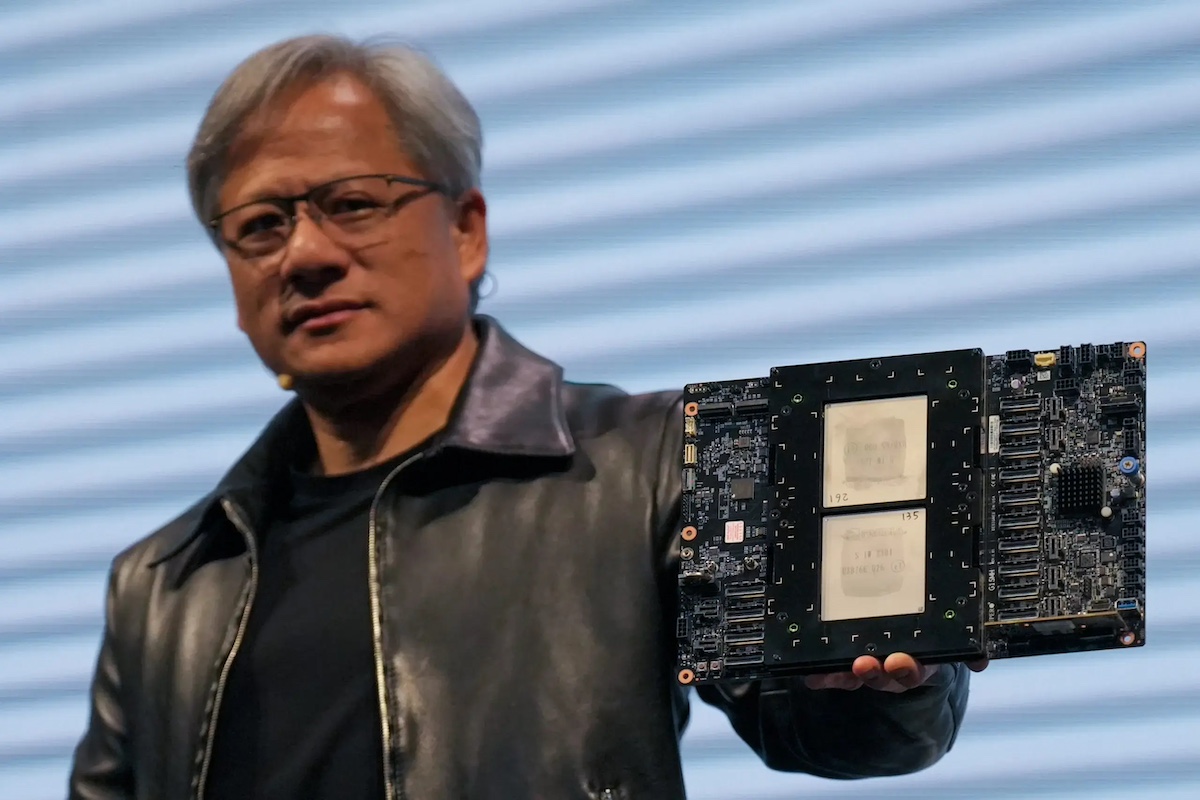

The December 8 decision, which permitted Nvidia to export its advanced artificial intelligence processors to Chinese markets subject to a 25% Treasury fee and strict customer vetting procedures, was initially framed as a pragmatic compromise. The administration presented it as simultaneously protecting national security interests while maintaining American competitiveness in the world’s largest AI market. However, Beijing’s response has been characteristically measured and strategic.

Chinese regulators convened emergency meetings with major technology firms, discussing potential limitations on access to foreign chips, including requirements for purchase justifications when domestic alternatives exist. This cautious approach underscores the fundamental miscalculation in Washington’s tech diplomacy: the assumption that China values access to American technology over autonomous capability.

The backdrop to this technological standoff is an evolved trade war that has transitioned from simple tariffs to sophisticated battles over supply chains and innovation. Earlier measures included a 20% ‘fentanyl tariff’ on Chinese goods—later reduced to 10% after negotiations yielded promises of stricter export controls on opioid precursors. China responded with temporary pauses on rare earth mineral restrictions and continued purchases of US agricultural products, suggesting a fragile detente.

Yet the semiconductor decision reveals deeper structural tensions. US export controls, progressively tightened since 2022, were designed to limit China’s AI advancement by restricting access to high-performance computing chips. Nvidia, which previously derived up to a quarter of its revenue from Chinese markets, had already developed downgraded versions specifically for these restrictions. Even these adapted products faced additional bans in September, forcing Chinese tech giants like Tencent and ByteDance to pivot toward domestic alternatives from Huawei and Alibaba.

Paradoxically, the restrictions have fostered remarkable innovation within China’s technology sector. Companies are optimizing algorithms to maximize performance from limited hardware, reducing dependence on cutting-edge imports. Startups like DeepSeek, founded by hedge fund veteran Liang Wenfeng, have emerged as disruptive forces, developing efficient AI models trained on restricted hardware through architectural innovations. Backed by state-linked funding, these enterprises exemplify how constraints have spurred adaptive development with global appeal.

Meanwhile, Huawei’s latest chips now power AI training at scales rivaling Nvidia’s older generations, supported by SMIC’s advances in mass production. Beijing’s Politburo has reinforced this direction with renewed calls for ‘core technology breakthroughs’ and billions in semiconductor investments.

The implications for American technological leadership are significant. Export controls risk isolating US firms from global markets while accelerating the development of competitive Chinese alternatives. Congressional efforts like the ‘Safe Chips’ bill, introduced by bipartisan senators to block eased restrictions for security reasons, may ultimately accelerate Huawei’s global expansion into European and African markets.

This technological confrontation mirrors China’s 2010 rare earth embargo against Japan, which prompted Tokyo to diversify its supply chains—exactly what is now occurring with semiconductors. Beijing’s current strategy aligns with President Xi Jinping’s ‘dual circulation’ doctrine: strengthening internal markets while engaging globally on more equal terms.

The broader lesson is one of unintended consequences. While US controls may have temporarily slowed China’s AI advancement by approximately two years according to some estimates, they have simultaneously seeded a leaner, more adaptive innovation ecosystem. As the H200 situation remains fluid, with potential for limited sales amid China’s self-reliance push, the United States faces a critical choice: intensify isolationist policies or recalibrate toward international alliances that establish joint technological standards with European and Australian partners.

The ultimate irony may be that Washington’s technological leverage strategy has provided Beijing with the perfect impetus to accelerate its own capabilities, transforming external constraints into domestic competencies one optimized algorithm at a time.