A comprehensive multinational investigation has uncovered a critical public health situation involving a European sperm donor carrying a dangerous genetic mutation that significantly elevates cancer risk. The anonymous donor, who began contributing sperm as a student in 2005, has biologically fathered at least 197 children across multiple European countries, with some offspring already developing cancer and several having died at young ages.

The investigation, conducted by 14 public service broadcasters including the BBC through the European Broadcasting Union’s Investigative Journalism Network, revealed that approximately 20% of the donor’s sperm contains a mutated TP53 gene. This genetic defect severely compromises the body’s natural cancer prevention mechanisms, resulting in Li Fraumeni syndrome—a condition associated with up to 90% lifetime cancer risk, particularly during childhood and for breast cancer in later life.

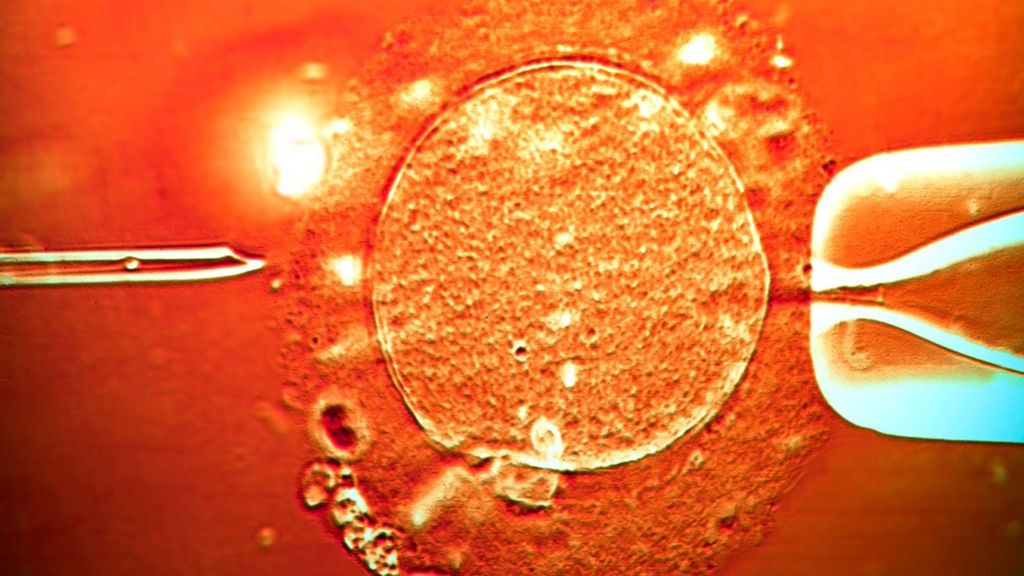

Despite passing standard donor screening protocols, the donor carried this mutation in a portion of his reproductive cells. Children conceived using affected sperm inherit the mutation in every cell of their body, creating a lifelong health vulnerability. Medical experts describe the situation as particularly devastating because affected individuals require annual MRI scans of the body and brain plus abdominal ultrasounds for early tumor detection, with many women opting for preventive mastectomies.

The European Sperm Bank, which distributed the genetic material, expressed sympathy for affected families while noting that neither the donor nor his biological relatives exhibit illness. The organization acknowledged that current genetic screening practices cannot proactively detect such mutations and stated they immediately blocked further use of the donor’s sperm upon discovery of the problem.

Distribution records indicate the sperm was utilized by 67 fertility clinics across 14 nations, with significant regulatory breaches occurring in several countries. Belgium, which limits donors to six families per donor, recorded 38 women producing 53 children from this single source. While the sperm was not directly sold to UK clinics, British authorities confirmed a “very small number” of families who sought treatment in Denmark have been notified.

This case has reignited debates about international sperm bank regulations and donor usage limits. Currently, no global standards govern how frequently a single donor’s sperm may be used internationally, with individual countries setting their own restrictions. The UK maintains a 10-family limit per donor, while the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology recently proposed a 50-family maximum—though experts note this wouldn’t prevent rare genetic disease transmission.

Reproductive health specialists emphasize that while such cases remain extremely rare compared to the overall number of donor-conceived children, they highlight systemic vulnerabilities in the global fertility industry. With approximately half of the UK’s sperm supply now imported from international banks, experts recommend prospective parents inquire about donor origins and usage history when considering fertility treatments.