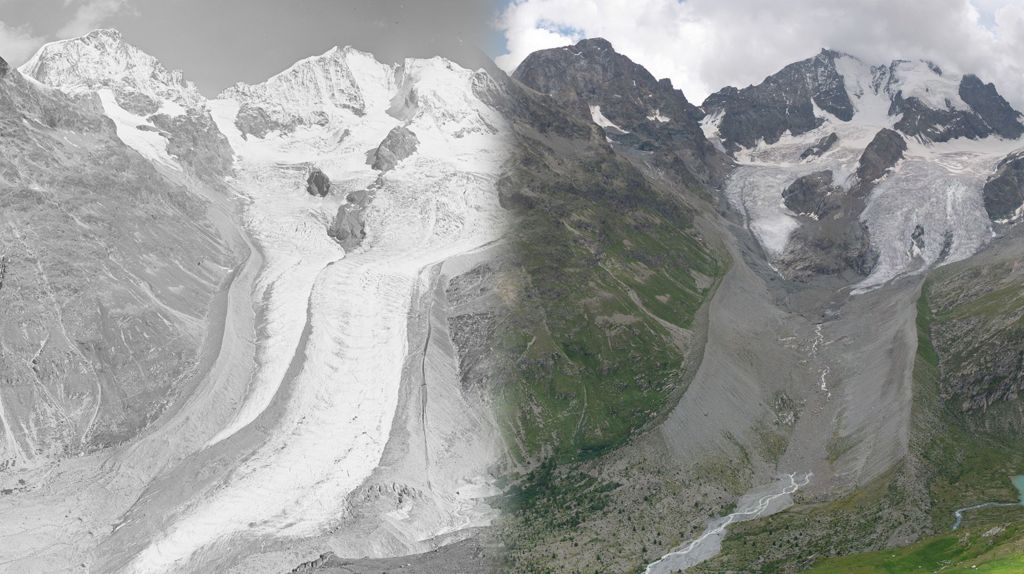

When Matthias Huss first set foot on the Rhône Glacier in Switzerland 35 years ago, the ice was a mere stroll from his family’s parking spot. Today, the journey takes half an hour, and the glacier’s retreat is a poignant reminder of the rapid changes unfolding across the planet. Huss, now the director of Glacier Monitoring in Switzerland (GLAMOS), recalls the glacier’s former grandeur with a sense of loss. ‘Every time I go back, I remember how it used to be,’ he says. His story is not unique. Glaciers worldwide are shrinking at an alarming rate, with 2024 alone seeing a staggering loss of 450 billion tonnes of ice outside Greenland and Antarctica, according to the World Meteorological Organization. This equates to a colossal ice block measuring 7km in height, width, and depth—enough to fill 180 million Olympic swimming pools. Switzerland’s glaciers have been particularly hard-hit, losing a quarter of their ice in the past decade. Satellite images and ground photographs starkly illustrate the transformation. The Rhône Glacier, for instance, now features a lake where ice once stood. Similarly, the Clariden Glacier, once in equilibrium, has melted rapidly this century. Smaller glaciers, like the Pizol Glacier, have vanished entirely. ‘It definitely makes me sad,’ Huss admits. The Great Aletsch Glacier, the largest in the Alps, has receded by 2.3km over 75 years, replaced by trees. While glaciers have naturally fluctuated over millennia, the accelerated retreat of the past 40 years is unequivocally linked to human-induced climate change. Burning fossil fuels has released vast amounts of CO2, warming the planet and destabilizing these icy giants. Even if global temperatures stabilize, glaciers will continue to retreat due to their delayed response to climate change. However, there is hope. Research published in *Science* suggests that limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels could preserve half the world’s mountain glaciers. Yet, current projections indicate a 2.7°C rise by the century’s end, risking the loss of three-quarters of glacial ice. The consequences are profound. Rising sea levels threaten coastal populations, while mountain communities dependent on glacial meltwater for agriculture, drinking water, and hydropower face dire challenges. In Asia’s high mountains, often called the Third Pole, 800 million people rely on glacial meltwater, particularly in the Indus River basin. ‘That’s where we see the biggest vulnerability,’ says Prof. Regine Hock of the University of Oslo. Despite the grim outlook, scientists emphasize the power of human action. ‘It’s sad,’ Hock reflects, ‘but it’s also empowering. If we decarbonize, we can preserve glaciers. We have it in our hands.’