A groundbreaking cancer treatment approach that forces malignant cells to reveal themselves to the body’s immune defenses has been developed by Chinese researchers, potentially overcoming the protective mechanisms that enable cancers to proliferate undetected. The innovative strategy, conceptualized as an ‘intratumoral vaccine,’ represents a significant advancement in immuno-oncology research.

The pioneering work emerged from a collaborative effort between Shenzhen Bay Laboratory and Peking University, spearheaded by principal investigators Chen Peng, Zhang Heng, and Xi Jianzhong. Their research, documented in the January 7 edition of Nature, outlines a sophisticated methodology that simultaneously dismantles cancer cells’ defensive barriers and marks them for immune recognition.

This novel approach addresses a critical limitation of existing immunotherapies. While current immune checkpoint blockade treatments attempt to release the biological brakes that restrain T-cells—the immune system’s specialized combat units—they frequently prove ineffective because cancers remain exceptionally adept at evasion. Clinical data indicates more than 60% of non-small cell lung cancer patients and over 70% of melanoma patients in China show minimal response to conventional checkpoint inhibitors.

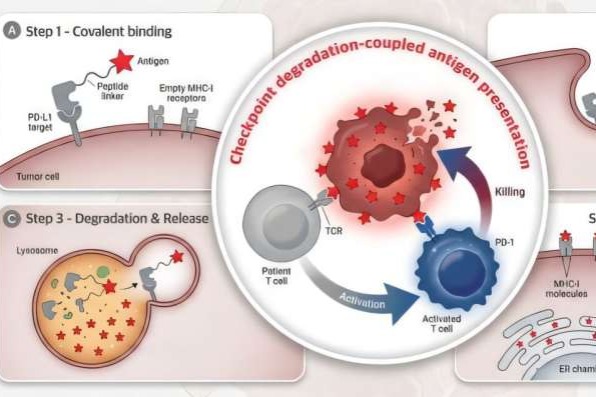

The newly developed technique leverages the GlueTAC platform, originally established by Chen Peng’s team in 2021 as a generalized system for membrane target elimination. The centerpiece of this breakthrough is the iVAC molecule, which executes two coordinated functions: degrading the PD-L1 protein that cancers employ as an immunological shield, while concurrently delivering viral-antigen markers to tumor cell surfaces.

This dual-action mechanism essentially tricks the immune system into perceiving cancer cells as virus-infected entities, thereby activating dormant T-cells that already possess viral combat capabilities. The resultant immune response triggers a targeted assault on the identified tumor cells.

Experimental validation using both animal models and patient-derived organoids—miniature lab-grown human cancer replicas—has demonstrated promising efficacy across multiple cancer types, including colorectal, gastric, and hepatic malignancies. Research teams are currently advancing preparatory work for translational drug development.

Despite the encouraging results, researchers acknowledge the substantial journey ahead before clinical application. Zhang Heng estimates a three-to-five-year timeline before human trials might commence, noting the considerable financial investment required and inherent uncertainties of medical research. The team maintains an openly collaborative stance, hoping to accelerate development and ultimately benefit cancer patients worldwide.